Composition vs Inheritance in Godot

Overview

When build software, it’s important to distinguish the difference between is and has when thinking about relationships between different concepts; is an engine a car? No, a car has an engine. Is a ‘Nissan Leaf’ a car? Yes! This may sound trivial but the distinction is important because getting this right in your games, and more broadly your software, can massively improve the way your projects scale and grow.

Composition Vs Inheritance

- Composition is the concept of defining what something does

- Inheritance is the concept of defining what something is

A case study, in Godot, where Composition can help you

Lets say we are making a sandbox game where the player can place objects into

the world, simple enough. Well we can start by abstracting objects that can be

placed into, lets say, an InGameObject.

We’ve just started building the game and want to keep things basic so we say that an in game object is going to be a static body; i.e. it can’t move.

public class InGameObject : StaticBody {

}

foo = "x"

bar = 123

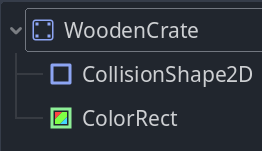

We begin to think of a few objects; a wooden crate for example.

public class WoodenCrate : InGameObject {}

Fantastic, we now have a base class which we can extend with any type of objects! We can add some behaviour to the base class such as a method to call when the object is actually placed.

public class InGameObject : StaticBody2D {

public virtual void Place(){

...

}

}

So now we create a scene for our wooden crate by

- creating a static body

- calling it “WoodenCrate”

- attaching the

WoodenCratescript to that static body

Now this works great! We can spawn these in and everything’s fine… until it isn’t.

Well if you’ve ever tried to build a game, you’ll inevitably want some fun interactive stuff in it, and these things often move around!

So we decide to add a bouncy ball into our sandbox. We create the class and

extend InGameObject.

public class BouncyBall : InGameObject {}

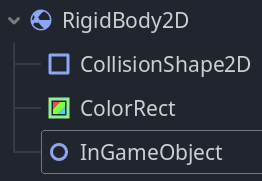

But then we realise something… a StaticBody2D isn’t going to work here. A

bouncy ball needs to be a RigidBody2D as it needs to move around dynamically.

We have tightly coupled our concept of an InGameObject to the concept of a

StaticBody2D.

This is the problem with inherritance, in this scenario, we have written the program in such a way that we have told the computer that a bouncy ball is a static body. What we wan’t to do is say that a bouncy ball is an in game object, but has the behaviour of moving around.

We should rewrite the base InGameObject class to say that an in game object

is a 2D Node, but doesn’t have any additional behaviour yet (i.e. being

static vs dynamic).

public class InGameObject : Node2D {

}

We can then still inherit our classes from the InGameObject class, because

they are in game objects, but we want to compose additional behaviour by

telling the computer what features they additionally have.

We can do this by changing how we think about our scene tree. We want to think in terms of what something is, and what behaviour it should have.

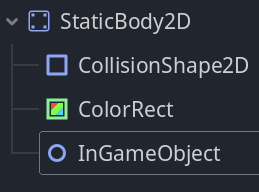

Back to the wooden crate and bouncy box. For our Godot scenes, we know that the

actual node for a wooden crate is a StaticBody2D and a bouncy ball is a

RigidBody2D. We Know that these nodes have the additional behaviour supplied

to them by our code, so we add (compose) that behaviour to them. We add a

Node2D to each scene and call it InGameObject and add the respective classes

we defined earlier to them.

Now we can have basically any Godot scene tree setup and we can add the behaviour of an in game object onto it! So your object could be static, dynamic, a texture etc.

Side note: The reason we name the child nodes InGameObject and not

WoodenCrate and BouncyBall is so we can abstract away the actual

implementation. When we are iterating over these objects in the scene, we can

tell if a scene has in game object behaviour by checking if it has any child

nodes called InGameObject.

It’s important to distinct here the nuance of is and has in respect to the

layers of our game, most notibly the Godot scene tree and our class definitions.

The actual Godot node for a bouncy ball is a RigidBody2D, but it has the

behaviour of an InGameObject composed onto it. And the concept of a bouncy

ball is an in game object, it can inherit that class because we are not

composing any behaviour onto the InGameObject class, a bouncy ball is

inherrently an in game object, but it isn’t inherrantly a Godot RigidBody2D.